How Employee-Owned Fashion Co-Ops Are Challenging Sweatshop Production

Worker-Led Co-Ops Are The Future

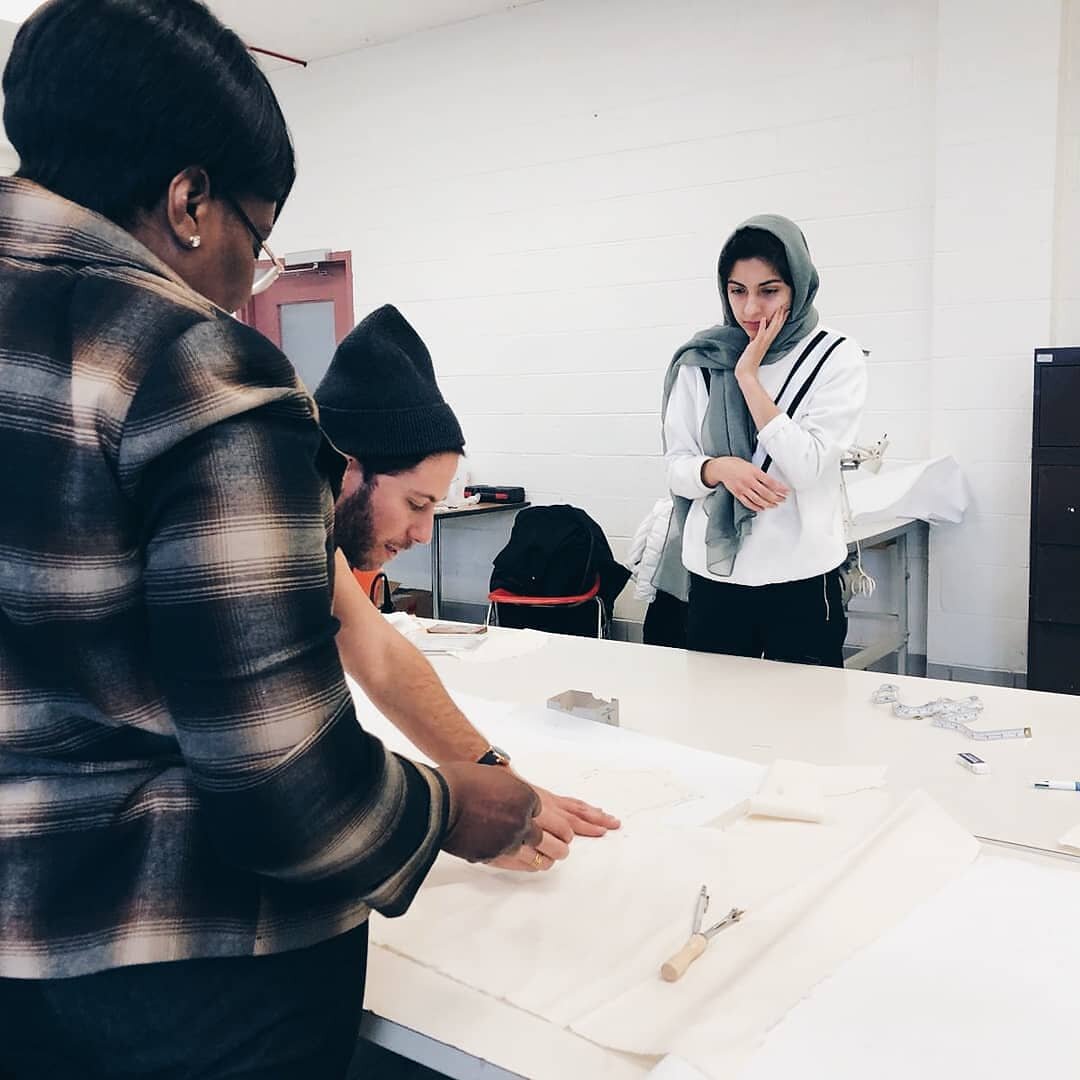

Hoda Katebi is fed up with sweatshops, and she’s doing something about it. I know, it’s a pretty bold statement. Especially seeing how the garment industry has been running on the exploitation of underprivileged workers for hundreds of years, but all big changes happen with a single first step. And hers is the launch of the Blue Tin Production Co-Op in Chicago, the U.S.’s first clothing cooperative run by refugee and immigrant women. It will officially open its doors this month.

“By ensuring that the garment workers are the ones that run, own, and profit off of their manufacturing co-op, there is less chance of abuse, exploitation, and the temptation to cut corners, creating dangerous working conditions.”

The creation of a worker-led co-op can disrupt the manufacturing industry because it will give designers truly transparent options when it comes to creating their collections. By ensuring that the garment workers are the ones that run, own, and profit off of their manufacturing co-op, there is less chance of abuse, exploitation, and the temptation to cut corners, creating dangerous working conditions. The fashion industry is worth an estimated 2.4 trillion dollars, and is filled with labor rights abuses. If more co-ops like this open, designers will be faced with two options: hiring production factories that are cheap in cost but with histories of abuse, or hiring the women-led co-ops that are guaranteed not to be sweatshops. Ethical fashion would be easier to produce and easier to shop.

Katebi is the Iranian-American founder of fashion and social action publication JooJoo Azad, and she’s made a career out of challenging fast fashion and fighting for garment workers’ rights. The co-op project began to take root when Katebi wanted to start her own socially-conscious clothing line, but then realized how difficult it was to find ethical manufacturing. Even the factories in Los Angeles are routinely shut down as sweatshops for exploiting undocumented Mexican workers. This brought Katebi to the realization that the only way to challenge the system was to put it directly into the hands of the workers.

“The only way to challenge the system is to put it directly into the hands of the workers.”

That’s where the Blue Tin Production Co-op comes in. Named after the blue Danish cookie tin that immigrant mothers use as sewing supply storage, the Co-op’s first launch is based in Chicago. It hires highly-skilled, low-income immigrant and refugee women and gives them non-patronizing, dignified work.

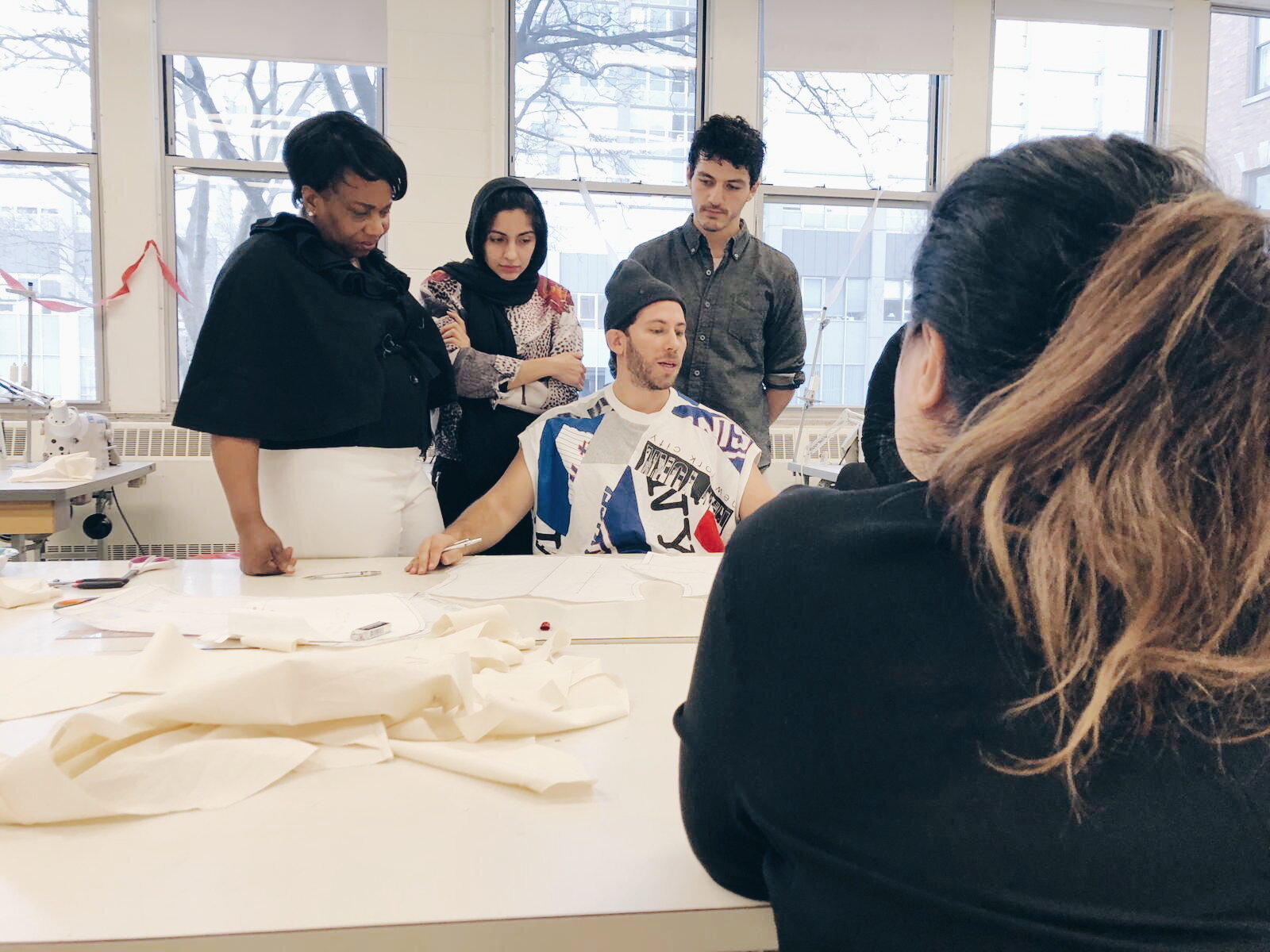

The women work full-time to produce clothes for designers, brands, and even department stores. Not only does Blue Tin employ these women, but it also provides mental and physical healthcare, legal and social services, child care, transportation, know your rights training, and even language services.

“A co-op is so necessary,” Katebi tells The Good Trade. “The garment industry has historically been plagued with violence and exploitation, and I wanted to create a space with a model that could as much as possible prevent even the possibility of repeating this violent history. Through a co-op structure, the members are all managers, and we all work together to determine every aspect of the co-op: from how the studio/workspace looks to the hours we work to the services we provide to ourselves and the community.”

All the members of the co-op carry intense trauma from their history, from losing spouses and children in war, to surviving domestic abuse, to being separated from their families. Throwing these women into underpaid jobs soon after landing in a new country gives them no time to process or deal with their pain. The co-op aims to fill all the needs of its members, not just the financial ones. Giving women the opportunity to run and manage themselves as a group gives them the chance to heal and and look forward.

“Giving women the opportunity to run and manage themselves as a group gives them the chance to heal and and look forward.”

And it works. Mercy, a founding co-op member, shared how the community has helped her rebuild. “I’m coming from an abusive relationship…and when you go through that, it brings you down. It makes you think you can not be nothing…telling you that you can never amount to anything. Coming to this co-operative, seeing these beautiful women, it gives you a sense of strength…it’s a blessing.”

In addition to revolutionizing working conditions and opportunities, Blue Tin Production also provides free certification-based sewing classes to the greater community of refugees, immigrants, and people of color looking to build their sewing skills, giving them the option to eventually join the Co-op or find a well paying, competing job elsewhere.

So what does this mean for ethical fashion as a whole?

Katebi is taking the guesswork and struggle out of the equation for designers who want to create clothes without exploiting people. And people are taking notice: the Co-op has already signed a list of designers and a soon-to-be announced department store, which will be creating an in-house line with the organization.

“We hope to, by working with large department stores, push for a greater shift in production that is transparent, ethical, and holistic. But more than that, we also want to be able to support independent designers who have such a difficult time finding manufacturing companies to work with when they have small minimums and slow production cycles. We want to be able to support and uplift slow fashion,” Katebi says.

“More broadly, we want to be able to set the bar in what clothing production can and should look like—but also, industry in general. Owned, run by, and managed by those doing the actual work on the ground, and especially those with the most needs.”

The Co-op is also working to educate us, the shoppers. It’s hard not to be swept away with the micro-collections and cheap price tags that fast fashion store windows tempt consumers with, but knowing what it takes to create these pieces can change minds. Because of that, the Co-op opens its doors to the public in order to raise the curtain behind the production.

“We want to be able to set the bar in what clothing production can and should look like—but also, industry in general.”

“It is so important for people to understand exactly what goes into creating a simple shirt, and why it shouldn’t cost five dollars,” Katebi explains.

For studio visits, Katebi likes to go through the process and lifespan of a shirt, from growing and harvesting the raw materials that make it all the way to its display in a store window. “Understanding the countless components, resources, and time that goes into creating something we take for granted—and we all indulge in—is shocking. I also bring in stories from my research and interviews with garment workers to personalize and go beyond just numbers and stats. The room gets terrifyingly quiet,” Katebi says. “As designers and consumers, we shouldn’t allow ourselves to justify or normalize violence in producing clothing.”

“As designers and consumers, we shouldn’t allow ourselves to justify or normalize violence in producing clothing.”

The Blue Tin Production Co-Op takes out the excuse of “I didn’t know” when it comes to the production system. Rather than going with low-cost factories that add to the bottom dollar, designers will have a truly transparent option that guarantees production workers are not only paid a living wage, but are thriving in their positions. These worker-led and owned co-ops will give designers and labels an easy alternative to the hazy ethics behind production factories. It takes the hurtle out of creating socially-conscious clothing, and ensures creators that the rights of workers are respected throughout their supply chain. The Blue Tin Production Co-op is a step in the right direction to begin dismantling that system.

You can help support the Blue Tin Production Co-Op and challenge sweatshops by donating to its crowdfund and following along on its Instagram!

RELATED READING

Marlen Komar is a fashion journalist who writes about how fashion and beauty can be a tool to implement change, push politics, and change public opinion. She is based in Chicago and has a thing for kimchi tacos.