We Interviewed 5 Changemakers Inspiring Sustainability

We’re in an era defined by pressing environmental challenges. More than ever before, the situation asks us all to consider how we can be more sustainable in our communities. To spark inspiration, we spoke to 5 changemakers (one is a duo, so technically 6!) all tirelessly striving to foster sustainable practices within their communities. They are all driven by a profound commitment to environmental change, and they’re catalyzing transformative action on a local level. Through innovation, advocacy, and grassroots initiatives — from advocating for BIPOC inclusion in birding to the creation of a decolonial travel guide — these changemakers help us envision a better future and show us how to actively realize it. Read on to hear their stories and get inspired yourself. 🌱

April Campbell, Founder of BIPOC Birders of MI

A lifelong lover of the outdoors and wildlife, April Campbell is the founder of BIPOC Birders of Michigan, on a mission to bring social diversity together with nature’s. Reacting to the lack of African Americans involved in outdoor nature activities, BIPOC Birders of Michigan introduces people of color to the world of birding. Bird by bird (or birder by birder), Campbell creates connection between nature and people of color, carving out a safe space for those traditionally excluded from the activity. BIPOC Birders of Michigan proudly declare they do see color — and they celebrate it, as they do all the colorful birds they spy through binoculars. We had the pleasure of speaking to Campbell about this particular worldview.

What does sustainability mean to you?

True sustainability, for me, is a recognition that humans are a part of and cannot exist apart from the natural world. Like most living creatures, we require water, food, shelter, and others of our kind to survive. If we accept that we are subject to the same biological and environmental forces as any other species, it encourages us to consume less and preserve more to ensure the continuation of a living planet into the foreseeable future. But this will not happen without sacrifice. It means buying less, driving less, flying less, and speaking out more!

Can you explain the importance of having diversity in bird-watching?

The demographics of the nation have changed markedly over the last 50 years. So have the politics. If we want to protect the birds for future generations, we must acknowledge we all are temporary travelers and consider what happens to the birds once we leave the scene. Political actors from communities with little exposure to the wonders of the natural world will have little incentive to protect it. It’s vital the birding community engage with marginalized communities, meeting them where they are and not expecting them to just show-up at a local Audubon meeting. Engaging urban populations in the study of birds and other animals in their environment helps us to know more about what urban bird populations exist, how they are faring or changing over time, etc. This is also a public health issue. Studies repeatedly show communities with green spaces and opportunities for outdoor recreation are healthier. It’s about caring for each other… and the birds.

What gives you hope for the future right now?

I must admit, I do vacillate at times between hope and despair over the planet’s dire status. But I remind myself, people, especially young people, are organizing all over the planet to end the destruction of our natural resources and slow climate change. They are protesting, volunteering, boycotting, and running for elective office. Here in the United States, we effectively have a plutocratic gerontocracy that will be difficult to dislodge, but it is happening and social media amplifies the voices of change. Young folks are savvy and they are aware of what’s at stake for us and the earth. That gives me a lot of hope.

Ashley Blakeney, Executive Director of Crenshaw Dairy Mart

Crenshaw Dairy Mart is a community collective supporting black and transnational identities in crafting a “new collective memory” that centers artistry and activism. By incorporating a deep understanding and respect of the Inglewood ancestry (the California city where the organization is based), embracing abolitionist principles, and centering healing at their mission core, Crenshaw Dairy Mart continually promotes solidarity in a community that has historically suffered at the hands of the racist carceral system. As the collective’s Executive Director, Ashley Blakeney works to promote local sustainability through CDM’s abolitionist artists’ residency program, various artistic programming, and numerous relief and mutual aid initiatives like the Inglewood community fridge and the abolitionist pod community garden. We discussed the importance of imagination for the future of sustainability with Blakeney, read on to hear more.

What does sustainability mean to you?

At the Crenshaw Dairy Mart, sustainability is deeply connected to abolitionist values and praxis. Sustainability centers around longevity, care, balance, reciprocation, and support. It’s the ability to have our needs met while continuing to meet the needs of our community and our world. Whether through the reciprocation of our Thich Nhat Hanh compost or the investment, care and love poured in the well-being of our staff, we approach sustainability as holistically as possible.

What role do art and abolition play in sustainability?

Imagination! I always say imagination is the cross-section of art and abolition. We must rely on our creativity to imagine new systems of care and imagine new ways of existing together. This process incorporates imagining pathways for sustainability in our relationships, communities, organizations, and larger collectives.

We live in a culture and society that doesn’t value imagination. Our current systems rely on instability, lack of care, and no imagination. When we relinquish our power and give up our imagination, both individually and collectively we destroy the possibility of sustainability. We must work together to change the current framework and that working together requires deep imagination practice.

Imagination, if regularly practiced, can set us free.

What gives you hope for the future right now?

The role of healing and abolition within the context of community building, especially within abolitionist institutions, brings an even deeper layer of hope for the future. Abolitionist institutions, like the Crenshaw Dairy Mart by their very nature, challenge existing structures of oppression and envision a world where art, justice, and care are central. The focus on healing within these spaces acknowledges the traumas inflicted by these structures and recognizes that transformation requires addressing and mending these wounds. At CDM we believe Incorporating healing into community building emphasizes the importance of not just changing systems externally but also nurturing individual and collective well-being. It’s about creating environments where everyone has the space to heal from the impacts of systemic oppression.

Lastly, by aligning with abolitionist principles, our communities actively work towards dismantling the systems that perpetuate harm. So many organizations in Los Angeles and across the country bring me hope. From Lauren Halsey’s community organization, Summaeverythang, to Question Culture, an abolitionist worker-owned media collective led by Richie Reseda and Rahael Asfaw, their approaches not only seek to remove oppressive structures but also to reimagine and rebuild a society based on mutual aid and care for all of us.

Hōkūlani Aikau & Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez, Authors of the “Detours: The Decolonial Guide Series”

“Detours” is a critical and ethical reinvention of the typical travel guide, created by Dr. Hōkūlani Aikau, Director of Indigenous Governance at the University of Victoria and Professor Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez of the Department of Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley. By centering places as culturally rich and historically complex — rather than fantastical tourist destinations — contributions by artists, activists, and scholars encourage visitors to practice sustainability and reflection in their contact with the sites and communities they visit. The series highlights the colonial legacy of tourism, offering readers a decolonial approach to travel and encouraging visitors to practice a holistic form of engagement with new places. We spoke to Aikau and Gonzalez about their work, and what keeps them going.

What does sustainability mean to you?

Our thinking about sustainability is grounded in Indigenous principles and practices, so this positions sustainability outside of capitalism and its extractive economy. In other words, it’s not about how much profit can be extracted from the finite resources available on this planet. Rather, it is about how we humans, especially those of us living in first-world nations who use more resources than humans in other parts of the world, can live in ways that actively contribute and add to the renewal and regeneration of the places that nurture us. This requires a major shift in mindset. Again, our mindset is grounded in Indigenous temporalities where decisions are made according to generational time horizons. Specifically, a relational framework requires humans to be attentive to the multiple temporalities of the natural world, and not just humans. For example, in Hawai‘i, the Koa tree is a culturally significant relative because they offer themselves as wa’a (canoes). When we consider the process of restoring the koa forests, we have to work within the temporality or life cycle of koa, which is approximately 100 human years.

What is giving you hope for the future right now?

We find hope in the poetry, prose, art, stories, and oral histories curated in these edited collections — these are the foundational acts for creating and sustaining communities in times of joy and celebration, and we turn to them especially in times of darkness and despair. Again, Indigenous teachings are instructive when thinking about futures and hope. Within a Kanaka ‘Ōiwi worldview, we, humans, stand firmly in the present moment looking to the past as we walk cautiously into the uncertain futures. What this means for us is that in times of crisis, we only need to look to ancestors and ancestral knowledge for lessons on how to live well and in the right relationship with all of creation.

How can we support “Detours” efforts around the world?

“Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai‘i” uses the narrative structure of a tour to tell decolonial stories of place. As editors, we now have a series that allows us to amplify and hold up decolonial and anticolonial practices taking place around the world. “Detours: Hawai’i” was the first in the series. We have decolonial collections in development focused on Palestine, Guåhan, Singapore, Korea, Okinawa, Puerto Rico, and the Indigenous Bay Area. We just got to see the full manuscript draft for the Palestine volume, which was both inspiring and heartbreaking in light of the genocide and utter destruction of Gaza.

We intentionally disrupt the guidebook as a genre and form, in order to challenge the assumptions about access to places that guidebooks promote. Rather, our series guides readers towards practices and principles that support and sustain decolonial and anticolonial visions that folks have for their homelands. Just as our approach to sustainability requires a critique of capitalism, the “Detours” series also takes seriously the damage of capitalism as well as militarism, heteropatriarchy, and white supremacy. Ultimately, doing away with these systems of oppression, exploitation, and death is really what sustainability will require.

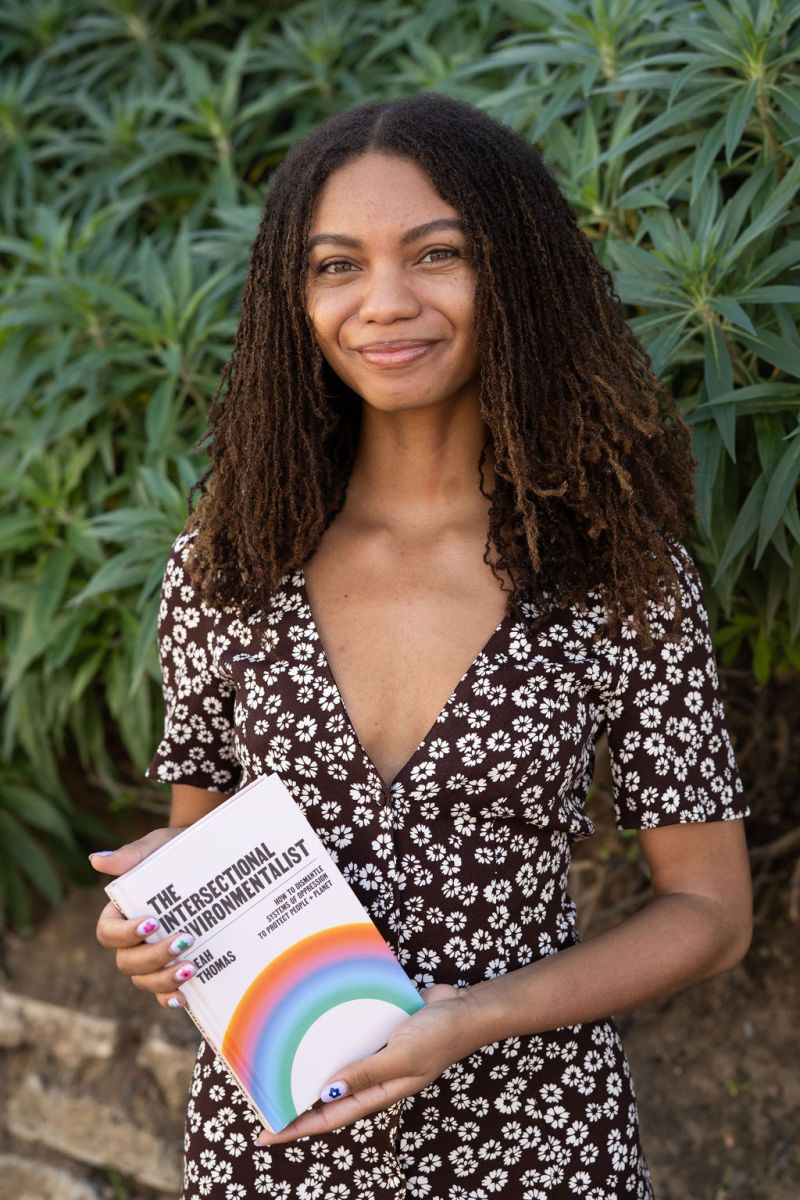

Leah Thomas, Founder of the Intersectional Environmentalist

The Intersectional Environmentalist is a non-profit platform and resource hub that advocates for environmental justice through education and the promotion of inclusivity and accessibility. As a champion of climate action, Leah Thomas (sometimes called Green Girl Leah) highlights the interdependence of social and environmental justice. Since the project’s inception in 2020, the Intersectional Environmentalist has connected numerous people to movements in their local community, empowered BIPOC environmentalists by highlighting their stories, and guided a variety of organizations to embrace intersectional environmentalism in their professional practice. We found out more about this approach to sustainability and how to think intersectionality alongside our efforts.

What does sustainability mean to you?

Sustainability means caring for myself, the planet, and my community in a way that is restorative and regenerative.

How can we center intersectionality in our fight for climate action?

Always asking the question “who” is being impacted by an environmental outcome or hazard and ensuring those most impacted have a seat at the table to advocate for their communities in decision-making.

What gives you hope for the future right now?

I have a lot of hope in grassroots environmental justice organizing and the power of a collective of people in a city to create change.

Nivi Achanta, Founder of The Soapbox Project

The Soapbox Project is a local, community-based social and environmental justice initiative with a mission to make climate action fun. Nivi Achanta, founder of the project, initiated programming that begins with education and always centers human connection and joy. In doing so, the Soapbox Project empowers the members of its community to create a more equitable and resilient future. Members of the Soapbox Project are guided by “bite-sized” weekly educational resources delivered to their inbox, and are provided meaningful spaces to connect both virtually and in person. The Soapbox Project helps its community turn climate action into an achievable goal — no matter how busy life gets. We had the pleasure of speaking to Achanta about mental health and sustainability, and how to move forward with courage and joy.

What does sustainability mean to you?

I’ve realized that my goal in life isn’t to “fight climate change” but rather create a world where each of us can live our best lives with our best friends on the best planet! When I think about sustainability, I think about environmental justice, cultural preservation, racial equity, and the intersections that enable us to continue existing on this beautiful, lonely planet.

How can we protect our mental health while fighting for climate justice?

At Soapbox Project, we believe that we can feel better by doing better. Our core values are courage and joy, and joy is a really important, underrated word in the climate movement. For us, it’s not just a byproduct of our work; it’s the foundation. If we’re not striving towards a joyful future, what exactly is it that we’re fighting for? It’s important to create space for “negative” emotions too, because none of us are going to get anywhere ostriching the problem away. I’m a huge believer in courageous spaces for anger, grief, and despair: spaces where we can process these things in community and then move through them together, to the action on the other side. One example of this is our Rage Room Action Hours. We gather in small groups, share the things we’re truly angry about, and simply hold space for each other until we’re ready to talk about the actions we want to take together. Also, especially in the United States, the mental health conversation is so individualistic. Soapbox (and I!) want to challenge that narrative by centering community care as a mental health solution. Prentis Hemphill shares, “The call is for community care and for an ethic, made clearer in this moment of instability, for care to be central in the systems we create. What can you offer? Where is your abundance? And where can you surrender into receptivity to become a beneficiary of another’s abundance?” Those questions guide me as I work on my own corner of healing our social and environmental fabric.

What gives you hope for the future right now?

Being in community with courageous people gives me hope. Hyperlocal activism gives me hope. Being able to plant seeds in my own neighborhood, both literally and figuratively, gives me hope. I’ve been shifting my own life from individual living to collective living: Through hosting Soapbox Seattle, through piloting a meal-share program with friends, through exploring cohousing and alternative models for the American Dream. It’s been beautiful to see how many people are done believing in the “default” path that’s been charted for us. The most crisp moment of hope came to me a few days ago, when I had a call with Abdul Semakula, a community builder in Kampala, Uganda. We were introduced by one of Soapbox Project’s Changeletter readers, and it turns out we’re doing very similar things on the theme of community healing, just in wildly different corners of the world. Seeing each person just do their best with what they have inspires me to continue doing my best too. Plus, the magical thing about not knowing what the future holds is…What if it’s the best-case scenario? Who knows!

Featured image is courtesy of Nivi Achanta

Sara Jin Li is an essayist, playwright, and filmmaker based in Los Angeles, California. She is also the founder of Heretics Club, a literary salon for creative writers. You can find her on Instagram at @sarajinli.